Table of contents

Did you think writing was going to be a breeze?

I did too, until reality hit.

I had always found writing easy and fun, but the deeper I got into the craft, the less I knew. As the novelist Thomas Mann says:

A writer is someone for whom writing is very difficult.

Fast forward 20 years and I now lead the writing program at one of the top universities in South Korea, where I've helped helped dozens of researchers get published and countless students get started writing online. But, wow, was it a grind.

Through these years of teaching academic and professional writing, I've discovered the biggest roadblock holding writers back: they see the elements of writing as a list of rules rather than a set of tools.

So to help you transform your writing and unleash your creativity, I'm sharing 31 writing tools I wish I’d discovered earlier and that'll help you connect with your readers.

Writing Tool 1: The Locomotive Effect

Here's a simple trick to make your writing so much more clear.

Because the difference between a clear sentence and a tangled mess that's overloaded with details all comes down to this one thing.

Take a look at this example of a clear sentence from Ryan Holiday’s Stillness is the Key:

The entire world changed in the few short hours between when John F. Kennedy went to bed on October 15, 1962, and when he woke up the following morning.

This sentence has a ton of details in it.

But it's clear because the core elements of the sentence are right up front. The first four words—“The entire world changed”—tells you straight away what's happening in the sentence.

But watch what happens when these core elements get buried under extra words in this next example from the same book:

Anyone who has concentrated so deeply that a flash of insight or inspiration suddenly visited them knows stillness.

See what happens when you separate the subject from the verb with too many details?

Here, 15 words separate the subject “anyone” from its verb “knows.” Since we read from left to right, the reader has to hold the subject in short-term memory for 15 words before the verb arrives, which is pretty hard work.

Clear writing is easy for the reader, so the first writing tool is the locomotive effect: When you've got a sentence with a bunch of details, put the subject and verb right up front.

That core clause–the subject and the verb–acts like an engine, and the rest of the details that follow hitch on to it like train cars–and that way, readers will choo- choo- choose you as their favorite writer.

Writing Tool 2: Make it Strange with Enallage

If you mean to make a mistake, is it really a mistake?

Amateur writers are really concerned with the notions of right and wrong, so they stick to safe language and are afraid to break the rules of writing.

But here’s the truth: great writers don’t just follow the rules—they bend them to create moments of strangeness.

Take the famous last lines from Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree. For context, I'll include the full paragraph, but watch what happens in the very last sentence...

Somewhere in the gray wood by the river is the huntsman and in the brooming corn and in the castellated press of the cities. His work lies all wheres and his hounds tire not. I have seen them in a dream, slaverous and wild and their eyes crazed with ravening for souls in this world. Fly them.

“Fly them.” Isn't that strange?

We don't fly people; we fly planes and helicopters. We can flee from people, and that's the literal meaning of the passage. But McCarthy went with “fly.”

An amateur might consider this a mistake, but pros can see very clearly what he's up to here.

We see the same thing in the poet Dylan Thomas’s famous line:

“Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Instead of using “gently,” Thomas opts for “gentle,” which is technically a mistake.

This use of deliberate grammatical mistake is the second writing tool, enallage, and expert writers use it to wrench readers awake.

Writing Tool 3: Write at a 5th Grade Reading Level

Have you ever heard that old writing tip: write at a 5th grade reading level?

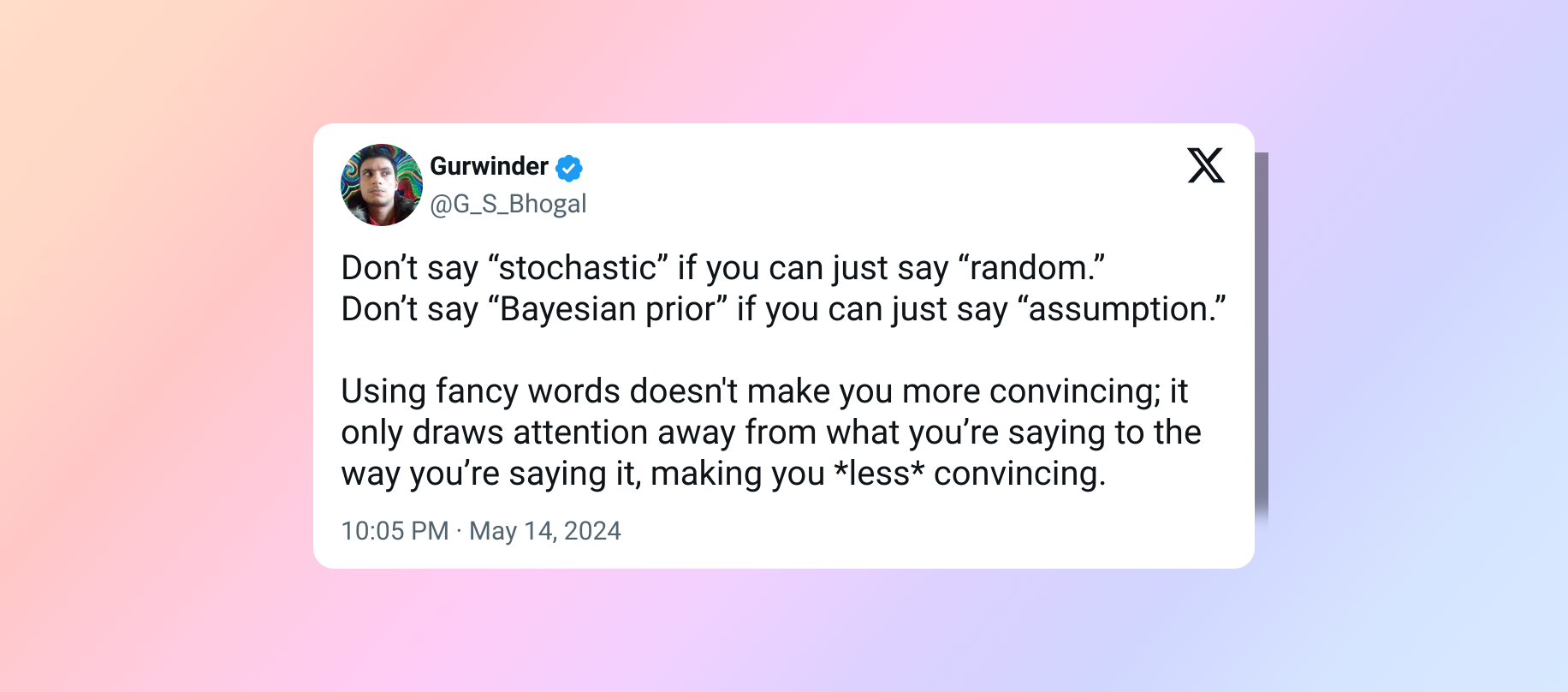

We see it all over the place, especially online. Here's Gurwinder:

If language is just about information, then Gurwinder would be right.

But of course it's not. Language is social as well, and your choice of words is not only about the content, it's also about your relationship with the reader.

If you always write at a 5th grade level, what does that say about how you think of your readers?

Richard Hanania makes this point perfectly when he writes about the difference between using ‘prior’ and ‘assumption’:

• I have a prior that every presidential election will be close.

• I have an assumption that every presidential election will be close.

They look similar, but prior comes from the world of Bayesian reasoning. If you say prior, you're delivering the same information as assumption, but you're also conveying your membership in a community that values statistics and analysis.

The same goes for stochastic versus random. Both mean unpredictable, but stochastic is a precise term used in statistics that shows you’re framing your idea from that specific perspective.

Always keeping it simple treats language like it’s just a vehicle for information.

But language is so much more than that. It's social.

So for the third writing tool, you can forget the rule about writing at a 5th grade level.

Of course, don't just choose puffy words for the sake of it, they make you sound like an ass. But do use those in-group codes that carry special meaning for your readers.

Writing Tool 4: Ten-Dollar Words

Speaking of simple: what kind of a writer are you?

Are you a Hemingway? A Faulkner?

Or are you more of a Mark fuckin’ Manson?

The writing styles of these American authors couldn't have been more different.

Faulkner once critiqued Hemingway for never daring to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.

Hemingway shot back:

Poor old Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? I know them all right, but there are older, simpler, and better words, and those are the ones I use.

Many people think Hemingway won this exchange, and his spare, clean writing style still lives on in American letters.

But Faulkner’s point is just as important: by sticking to simple language, we risk underestimating our audience and dulling our own creative edge.

Plain language is great for connecting with readers, but sometimes the right word can really make an idea pop—even if it sends someone to the dictionary.

So Writing Tool #4 is a two-parter:

First, don't be afraid of those 10 dollar words.

I've been sent to the dictionary plenty of times by Cormac McCarthy and James Joyce, and I've never regretted the journey.

Second, don’t be afraid of those cheap words either.

Look at Mark Manson’s best-selling book, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck. You won’t find language like that in the works of Hemingway or Faulkner, but that book became a best seller because it used language that resonated with his readers.

There are no universal rules for writing because there are no universal readers. Writers don’t have a general audience; they have specific readers, and when you know who those readers are you can use their coded language to signal your in group status.

Writing Tool 5: Ironic Juxtaposition

Moving on from vocabulary, let’s look at a technique for building tension by looking at examples of it in poetry and Monty Python.

Take, for instance, the opening lines of T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky,

Like a patient etherized upon a table

Those first two lines are classic enough; they invite the reader to a romantic evening's stroll.

But that mood is shattered by that third line: a patient etherized upon a table.

What are these two images doing together?

We see the same writing tool at work in the classic scene from Monty Python's Life of Brian, where everyone being crucified joins in to sing “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

The contrast between the cheerful song and their morbid death sentence, just like the contrast we saw in the T.S. Eliot poem, joins two writing tools together.

The first is juxtaposition, which just means placing two things side by side to highlight their similarities or differences.

The second is irony, when the literal meaning splits apart from its meaning in context.

Join them together, and you get ironic juxaposition–when you place two objects side by side, so that each one changes how you see the other–and that's the fifth writing tool.

Writing Tool 6: Alliteration

Some sayings sound so smooth, they stay stuck in our skulls forever.

For example, there's that famous line from the Great Gatsby:

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

What’s the secret sauce? Stick around to see how to use simple sounds to shape super strong sentences!

If you’ve ever heard expressions like…

- “Curiosity killed the cat.”

- “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

- “It takes two to tango.”

…then you’ve already experienced a writing tool that makes any phrase memorable—even if the meaning is total nonsense.

We naturally love words that start with the same letter; they roll off the tongue.

But it's not just that they sound good; this writing tool actually makes these phrases more persuasive–even if the meaning is total nonsense. As Mark Forsyth points out:

- Curiosity did not kill the cat.

- Nobody has ever thrown a baby out with the bathwater.

- It takes two to tango; but two to waltz as well.

But those sayings still hang around as true, and the line from Gatsby is so memorable, not because they are true, but because they sound true–and that's the power of the sixth writing tool: alliteration.

Writing Tool 7: The Ladder of Abstraction

Speaking of Gatsby, let's take another look at that famous passage.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter-to-morrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther…And one fine morning- So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

That green light–what's it doing there? What does it mean to believe in a green light?

In this passage, the green light isn’t just the light at the end of Daisy’s dock—it becomes a powerful symbol of the American Dream. And the way it transitions from a tangible image to an abstract idea is an example of the 7th writing tool: the ladder of abstraction.

At the bottom of the ladder, you find concrete images—things you can touch, see, and smell; something you can picture in your mind or stub your toe on.

Climb a few rungs higher, and you’re dealing with abstract concepts like freedom, greatness, and the American dream.

The trick is to balance these levels.

Sometimes writers get too caught up in the top layers, and their writing feels disconnected from reality.

Other writers will spend all their time down near the bottom, and their work feels mundane, like journalism. It feels like it doesn't carry any transcendent meaning.

So as you write, balance out your ideas by moving up and down the ladder of abstraction–our seventh writing tool.

Writing Tool 8: Polyptoton

This next writing tool is more common in music, but you can use it to write pithy, memorable lines.

Remember when Jay Z said:

I'm not a businessman; I'm a business, man.

Or when the Beatles sang:

Please, please me like I please you

…come to think about it, what were they singing about there?

I do all the pleasing with you

It’s so hard to reason with you

Why do you make me blue?

Last night I said these words to my girl

I know you never even try, girl

Come on, come on

Please please me, woah yeah, like I please you

But it's not just in music; even Carl Jung used this writing tool when he said:

The healthy man does not torture others—generally it is the tortured who turn into torturers.

The thing that makes these lines so catchy and powerful is all thanks to a technique that uses a single word in various parts of speech—a technique called polyptoton, from the Greek for “many cases.”

By repeating the same word in different structural places, it makes the reader do a double take and leaves your words hanging in their ear.

Writing Tool 9: Antithesis

But if you're trying to make a line sound powerful and deep, the best way isn’t to be original—it’s to take what’s ordinary and turn it upside down.

One master of this writing tool was Oscar Wilde, who was famous for his witty one-liners that we still quote today.

“Fashion is what one wears oneself. What is unfashionable is what other people wear.”

“Journalism is unreadable, and literature is not read.”

“Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.”

As a writing teacher, I feel personally attacked.

The formula of these lines is straightforward: X is Y, and not X is not Y.

It starts with a familiar idea, then flips it in an unexpected way. That sudden contrast is what makes these statements so striking.

Side Note: The Semicolon

Many people hate the semicolon because they don’t know how to use it, and in many cases you’d be better off not using it.

But this rhetorical device is the perfect place to use a semicolon.

The negative and positive side of the statement don’t belong in separate sentences; they belong together in the same sentence, like two sides of the same coin.

But you can’t join two statements with a comma, so instead you can use a semicolon.

This technique is called antithesis. If you want to assert something forcefully, try inverting it. The reason this works is because it covers both sides–of what's true and what's not true–which ties in quite well with our next writing tool:

Writing Tool 10: Merism

Ladies and gentlemen—

Wait a minute… Why do we say “ladies and gentlemen” instead of simply “everyone”?

Or what about wedding vows: why do we say “in sickness and in health, for richer or poorer” when we could just say “always”?

Or think about the phrase “searched high and low”—why not just say “everywhere”?

Well there's actually a trick behind them that, once you learn it, you’ll start spotting it here, there, and everywhere.

We do this all the time:

- “Through thick and thin” instead of in all circumstances.

- “In times of war and peace” instead of always.

- “In the beginning god created the heavens and the earth”… so, everything?

These examples break the rule of brevity: don't say in several words what can be said in fewer. So what is it about these longer examples that hits harder?

It's because each of these examples uses two opposite things to mean everything in between. Referencing the whole by its extremes tricks our brain into feeling like you’re covering every possibility in between, which is a clever trick called merism–our tenth writing tool.

Writing Tool 11: Synaesthesia

For the 11th writing tool, we're going to tap in to a bit of reader psychology.

When you understand how your reader processes your writing at a cognitive level, you can shape your prose to create certain effects.

Take a look at this line from a Raymond Chandler story:

She smelled the way the Taj Mahal looks by moonlight.

What is it about this image that hits you a lot harder than simply saying “she smelled like patchouli.”

Or how about that famous scene from Apocalypse Now:

I love the smell of napalm in the morning. Smells like victory.

What makes these lines so vivid and memorable?

So, you know how you might be walking down the street and you catch a whiff of something and you're brought back to a vivid memory from long ago? Smell has such a strong relation to memory because the part of the brain that processes smells connects directly to our memory and emotion centers.

One of language’s most powerful tools is its ability to mix up the senses. We can use a familiar image to describe an unfamiliar smell, or a familiar smell to describe an abstract idea.

We do this all the time:

- a cold stare

- a gravelly voice

- the sweet taste of victory.

These are examples of synaesthesia—using one sense to describe another. They let us feel a voice, see a sound, or even smell an emotion.

As David Abram notes, synesthesia is not an aberration; it’s the primary layer of experience:

When, for instance, I perceive the wind surging through the branches of an aspen tree, I am unable, at first, to distinguish the sight of those trembling leaves from their delicate whispering. My muscles, too, feel the torsion as those branches bend, every so slightly, in the surge, and this imbues the encounter with a certain tactile tension. The encounter is influenced, as well, by the fresh smell of the autumn wind, and even by the taste of an apple that still lingers on my tongue.

So if you're writing about an idea, try to ground it into something more concrete by blending it with one or more of the senses.

Writing Tool 12: Diacope

Remember that famous line from The Wizard of Oz where the Wicked Witch of the West supposedly cries, “Fly my pretties, fly!”?

Really? That's odd–because she never actually said that.

What is it that made so many people mis-remember this iconic line?

Here's the same writing tool used in another famous scene that you surely remember:

–I admire your courage, Miss…

–Trench. Sylvia Trench. I admire your luck, Mr…

–Bond. James Bond.

The thing that makes these lines so iconic is thanks to a writing tool called diacope, a technique where a word or phrase is repeated after a brief interruption.

Once you learn diacope, you’ll start to see it everywhere.

I once read a paper in the field of cognitive linguistics that was studying various rhetorical devices that were used in English and Russian literature from the 19th-21st centuries. Diacope was by far the most common, occurring between 800-9,000 times per text.

Why is it so popular? What makes it work?

The repetition creates a verbal sandwich that etches the the line into your memory.

There are a few variations:

Vocative Diacope:

“Drill baby drill.”

“Zed’s dead, baby. Zed’s dead.”

Elaboration Diacope:

“Sunday bloody Sunday.”

“O Captain! My Captain!”

Extended Diacope:

“Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”

“Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty we are free at last.”

Diacope. Diacope. All the best one-liners use diacope.

Writing Tool 13: Epistrophe

There's an unforgettable speech in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath:

Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beating up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad and—I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready. And when our folk eat the stuff they raise and live in the houses they build—why, I’ll be there.

See how he keeps returning to the core message after adding in long sets of details?

That’s epistrophe: a technique where you repeat the same word or phrase at the end of successive clauses or sentences.

Like the chorus of a song, epistrophe helps your readers stay focused on your core message.

Writing Tool 14: Prolepsis

They fuck you up, your mom and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

That famous line from the poet Philip Larkin uses a little grammar trick that you can use to launch the reader into the rest of your story.

It's the same writing tool that we see at the start of Ernest Hemingway's Old Man and the Sea:

He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty-four days without taking a fish.

In fact, this writing tool is so powerful that we even find it in that classic opening to all scary stories: It was a dark and stormy night…

What these lines have in common is that the first word is an ambiguous pronoun. Normally, pronouns link backwards to a noun that has already been mentioned. But in these examples, the pronoun links forwards, to a noun that hasn't yet been introduced.

Readers cannot tolerate that ambiguity; it opens a loop that they want closed–who fucks us up; who was the old man? These questions spark curiosity, pulling readers in to the story.

This clever writing tool is known as prolepsis. By starting with an ambiguous pronoun, you motivate your readers, launching them straight into the heart of your story.

Writing Tool 15: Congeries

When David Foster Wallace wrote about his experience aboard a cruise ship, he didn't just describe it—he drowned you in the details.

And that flood of details is exactly why his essay A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again became a nonfiction classic.

Here are just a few lines from the famous opening:

I have now seen sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. I have seen an all-red leisure suit with flared lapels. I have smelled suntan lotion spread over 2,100 pounds of hot flesh. I have been addressed as "Mon" in three different nations. I have seen 500 upscale Americans dance the Electric Slide. I have seen sunsets that looked computer-enhanced. I have (very briefly) joined a conga line. I have seen a lot of really big white ships. I have seen schools of little fish with fins that glow. I have seen and smelled all 145 cats inside the Ernest Hemingway residence in Key West, Florida. I now know the difference between straight bingo and Prize-O. I have seen fluorescent luggage and fluorescent sunglasses and fluorescent pince-nez and over twenty different makes of rubber hong. I have heard steel drums and eaten conch fritters and watched a woman in silver lame projectile-vomit inside a glass elevator. I have pointed rhythmically at the ceiling to the two-four beat of the same disco music I hated pointing at the ceiling to in 1977.

The sequence of these images is disjointed, sometimes surprising, but they all come together to form a tapestry that establishes a rich context.

And that was only the opening paragraph, but after two pages of these images, you really get the feeling that you're standing there on deck with the author.

This flood of sensory details is an example of a writing tool called congeries—a rhetorical strategy that piles up adjectives, nouns, and images to create an immersive, almost overwhelming experience.

Writing Tool 16: Steal Style

This writing tool was passed down to me from my thesis advisor in university. It's something he discovered whenever he was working on his PhD.

His dissertation supervisor was Walter Benn Michaels, an academic literary critic who is very well known for being an outstanding writer and stylist. You don't even have to be interested in American lit to enjoy his writing; his writing is so clear, his arguments rock solid, and he just knows how to make ideas pop off the page.

So you can imagine, if this was your supervisor, you might feel a little timid about the quality of your own writing. Especially among academics, who basically write arguments for a living, it was important to not only have new, important ideas, but to also be able to write about them with clear style.

And that's when my thesis advisor developed this secret trick: steal style.

Stealing style is a way of bringing a writer's voice into your own. To steal style, you find a writer you admire, analyze the their sentences and sections, and try to slot your own ideas into those structures.

And when he started doing this, he felt a little nervous when bringing one of his chapters to his advisor for feedback. But lo and behold, his advisor was praising him as a good writer, and he said that he kind of sat there thinking Oh my god, you don't even realize it, these are your sentences.

Of course, we're talking about style here, not ideas. Ideas are under copyright, but style is open source, yours for the taking.

So if you want to steal style, here’s a quick exercise:

- Ask a few writer friends which authors they admire and why.

- Pick a couple of articles or stories from those writers and find a phrase or passage that stands out to you.

- Read it two or three times and–this part's important–close the book and try to write out the section that you just read.

- Start with individual sentences, but try to work up to chapters and maybe even pages.

The more you do this, the more their writing style will seep in to your own.

Writing Tool 17: Collect Scraps

Here's what Kendrik Lamar told Rick Rubin about how he writes:

I have to make notes because a lot of my inspiration comes from meeting people or going outside the country, or going around the corner of my old neighborhood and talking to a five-year-old little boy. And I have to remember these things. I have to write them down and then five or three months later, I have to find that same emotion that I felt when I was inspired by it, so I have to dig deep to see what triggered the idea… It comes back because I have key little words that make me realize the exact emotion which drew the inspiration.

There's nothing systematic about this; these little scraps of paper just pile up. You don't know where it's leading you when you're writing it down, and you might never use it again.

Some of them become orphans, but others begin to cluster and aggregate about larger ideas, and as a writer you'll start to spot the through line that links them in a constellation.

And that's how these little scraps of paper become ideas of your own.

Only it's much easier for us today, because we don't have to haul around these shoe boxes full of notes.

Personally, I love to use the app Obsidian–it's free, open source, and it doesn't store your files on a server, meaning you never have to worry about data loss or privacy. But more important is the architecture of the app: unlike Notion, which is organized hierarchically with these nesting pages, Obsidian is designed to be horizontal. At any moment, any note can be linked to any other. So any time you create a new note, you can just chuck it in the vault and forget about it until one day, weeks or even years down the road, when something new occurs to you and you want to pull it up.

It's the perfect app for this messy, chaotic note-taking practice, and it's what I recommend you use for this writing tool, which I call collecting scraps.

Writing Tools 18 & 19: Telling Stories about Characters and their Actions

This story has a problem:

One day, as the watching of an informative and entertaining YouTube video was taking place on the part of a clever writer, the creator's subtle request to like, share, and subscribe occurred, causing the clever writer amusement.

We prefer something more like this:

One day, a clever writer was watching a YouTube video that was informative and entertaining, when the creator subtly requested her to like, share, and subscribe, which amused her.

What makes that one better than the first? To see the two writing tools at work here, ask yourself two questions:

- What’s this story about?

- What’s going on here?

What's this story about?

Obviously, this story has two main characters: a clever writer (that's you) and the video creator.

In the first example, these characters are tucked away in these subordinate positions:

One day, as the watching of an informative and entertaining YouTube video was taking place on the part of a clever writer, the creator's subtle request to like, share, and subscribe occurred, causing the clever writer amusement.

In the second, they're placed more prominently in the hierarchy of the sentence:

One day, a clever writer was watching a YouTube video that was informative and entertaining, when the creator subtly requested her to like, share, and subscribe, which amused her.

So the first writing tool at work here is to make the main characters the subjects of verbs.

What's going on here?

What's happening in this story?

You'll find that the main actions are watching, requesting, and amusing.

In the first case, these actions are expressed in nouns:

One day, as the watching of an informative and entertaining YouTube video was taking place on the part of a clever writer, the creator's subtle request to like, share, and subscribe occurred, causing the clever writer amusement.

In the second case, these actions are seated in the verb, which is the heart of the sentence:

One day, a clever writer was watching a YouTube video that was informative and entertaining, when the creator subtly requested her to like, share, and subscribe, which amused her.

So the second writing tool is: place specific actions in verbs, not nouns.

Writing Tool 20: Start Your Engines

Do you remember that great scene in No Country for Old Men, when Llewelyn Moss finds that briefcase stuffed with money?

Side bar: you've got to read the book. Yeah yeah, everyone says the book is better. But the interesting thing about No Country for Old Men is that McCarthy first wrote it as a screenplay; it was rejected, so he adapted it into a novel, which the Cohen Brothers then picked up for a movie. But because the novel was first a screenplay, it's incredibly spare. Reading it is like admiring a great engine, simple and compact and elegant in its structure and design.

And speaking of engines: The reason that scene with the briefcase is so incredible is that it functions as the engine of the story.

That one moment when he discovers the money is the start of the tragedy, the first domino in line. It immediately raises questions:

- Will he take the money?

- Who does it belong to?

- Will he get away with it?

…Questions that demand answers and hook you in for the rest of the story.

That one moment is the engine of the entire story—it fires up the narrative and keeps you riveted, eager to see how every twist unfolds.

When you’re writing your own story, you should be able to point to that one moment in the opening that serves as your engine, the one that drives forward the rest of your story as it drags your reader behind.

Writing Tool 21: Problem Statements

Now, for a harsh truth that will hopefully help you write in a way that readers will find engaging and valuable–and that's the key word: value.

So much writing advice focuses on the formal elements of writing. It says that writing should be clear, organized, and persuasive.

But guess what?

- If your writing is clear and useless, it's useless.

- If your writing is organized and useless, it's useless.

- If your writing is persuasive and useless, it's useless.

Readers don't care about clarity, organization, and persuasion. Those elements are just the vehicles of delivery.

But ultimately your writing needs to do one thing: deliver value.

So what is value? It sounds like an abstract thing, but in fact it's very clear and precise.

Readers perceive writing as valuable when it solves a problem that they care about.

I don't mean to sound too utilitarian about that. Of course, we do all kinds of things in our writing–there's self-expression, and writing about ideas and opinions.

But the fact is that if those things aren't motivated towards solving a problem that the reader cares about, then nobody is going to read about it.

So the writing tool here begins with a mistake: don't write about topics. Nobody cares about topics. If you start off with 'In this piece I will explore the topic of...' then the reader has already left the building.

Instead, at the top of your page you should be able to fill out a problem statement like this:

I am writing about (topic) because I want to find out (question) in order to help my reader (gain benefit / avoid consequence).

Writing Tool 22: Dying Metaphors

Garbage collectors in New York City have a special term for the maggots they find in the trash: disco rice.

This is about as good a metaphor as you can ever hope to find.

But even if you can't write a metaphor this good, do your best to avoid clichés–they drain the life out of your writing.

George Orwell warns us that relying on cliches is a shortcut, a substitute for creative thought. In his book Politics and the English Language, he argues that bad writing is the result of bad thinking, and that bad writing has a corrosive effect on civilization. In it he singles out cliches, which he calls “dying metaphors” that

have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves.

If Orwell is right, then writers have a civic duty to keep our language vigorous and alive, actively responding to and reflecting our culture. Using dying metaphors–clichés–is empty tawk. They don’t mean anything.

But the role of the writer has always been to detect the signs of cultural change, saying what people think before they realize it and offering up these images to the culture.

So Writing Tool #22 is, beware the cliché.

Writing Tool 23: Understate the Serious

Speaking of Orwell, he also said that good writing should be like a windowpane—so clear that readers see the world, not the writer.

In other words, the best writing doesn’t draw attention to itself; it simply lets the story shine through.

This idea is especially important when dealing with heavy subjects. Here are two approaches, from the filmmaker Steven Spielberg:

First, in Schindler’s List, the horrors of the Holocaust aren’t exaggerated or sensationalized. Instead, the film relies on quiet restraint, allowing the silent suffering to speak for itself. The result is haunting.

Compare that to Saving Private Ryan, where Spielberg takes the opposite approach. The opening D-Day sequence throws you into the chaos of war with brutal, unrelenting detail. Every explosion, every wound, every moment of terror is laid bare.

Both films are powerful, but for different reasons.

The restrained style of Schindler’s List engages the imagination, forcing the audience to imagine the worst, filling in the gaps with their own horror.

Meanwhile, Saving Private Ryan leaves nothing to the imagination—it shows everything.

In writing, you don't need to lay it all out. When dealing with serious subjects, step back and let the weight of the story do the work. But if the topic is light or playful, feel free to lean in, add some flair, and make your presence known.

Understate the serious, and overstate the light. Let your tone match the weight of your subject, and your writing will carry that much more impact.

Writing Tool 24: Interesting Names

Writers have a sweet, almost compulsive addiction to interesting names.

Think about the unforgettable characters in literature: Humbert Humbert from Nabakov, Rick Vigorous from David Foster Wallace.

But the real king of characters with interesting names is Thomas Pynchon. Here are the top 10 names of Pynchon characters:

- Tyrone Slothrop (Gravity's Rainbow)

- Mike Fallopian (Crying of Lot 49)

- Meatball Mulligan (Entropy from Slow Learner)

- Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke (Mason & Dixon)

- Pig Bodine (V, Gravity's Rainbow)

- Slab (V)

- Scarsdale Vibe (Against the Day)

- Benny Profane (V)

- McClintic Sphere (V)

- Sauncho Smilax (Inherent Vice)

Bonus name: I grew up not far from a village called St Louis de Ha! Ha! – yes, with exclamation points – and I always felt like that town was a story waiting to be told.

And that's writing tool 24: to collect interesting names and let them invite you to write their story.

Writing Tool 25: The Bilbo moment

Think about how The Hobbit begins.

Gandalf doesn’t just throw Bilbo into a chaotic adventure right away. First, he secures Bilbo’s commitment—giving him just enough time to feel (somewhat) comfortable before the real journey begins.

As writers, we should do the same for our readers.

Before you dive in deep, you need to build trust. That means starting with examples that are clear, simple, and easy to grasp—something your reader can confidently nod along to.

You'll find this in most popular non-fiction, but consider for example Sam Harris's Waking Up, which is an argument about how to have spirituality without religion. It's a complex argument that involves neuroscience, religion, ethics, and it can at times be demanding. But the book starts off with a vivid story about going on an overnight camping trip as a teenager, and later taking a trip to Nepal, that would completely transform his view about our place in the cosmos.

That simple, captivating story opens up the conceptual space in which his argument will unfold.

And that's what I call a Bilbo moment: a straightforward, concrete example that lays the foundation for everything that follows.

As time goes on, Gandalf brings Bilbo into a world of dwarves, quests, and dragons; likewise in nonfiction, you can start introducing more abstract ideas, metaphorical connections, and deeper insights, but only once your reader is on board.

Be Gandalf: guide your reader from familiar territory into the more intricate, transformative terrain of your world.

Structure your examples from simple to complex, from literal to metaphorical. Lay the groundwork with clear, accessible evidence, and then build on it, stretching your argument with nuance and depth.

Begin with your Bilbo moment.

Writing Tool 26: Write like Zappa

The legendary musician Frank Zappa nailed it when he complained that most guitar solos are played the same way every night—mechanically practiced until they lose all the magic.

Zappa never rehearsed his solos; he never knew what he'd play until the moment he started playing.

I have a basic mechanical knowledge of the instrument, and I got an imagination, and when the time comes up in the song to play a solo, it’s me against the laws of nature.

That’s the spirit you need when you write.

When you sit down to create, don’t overthink every word until it’s perfectly rehearsed. Instead, set a fixed piece of time—say, twenty minutes—take a deep breath, and let it rip. Treat that interval like a live solo: unpredictable, raw, and full of the thrill of improvisation.

You have basic knowledge of the instrument (grammar and vocab), you've got imagination, and you've got taste.

So when the time comes to write, rip a solo and leave the results to nature.

Of course, it wont' be spotless. But the best stuff never is.

Writing Tool 27: A-A-B, Not A-B-A

In comedy there's the classic rule of three—set up a pattern with two beats, then hit your punchline with a twist.

In nonfiction writing authors sometimes develop an idea using the A-B-A structure—presenting an example, then a contrast, and then circling back.

But with this structure, the reader never gets a chance to fully grasp the core idea before it’s muddled by the contradiction.

So instead, start by presenting two similar examples that clearly hammer home your key point (that’s your A-A). Only after your reader has soaked in that idea do you introduce a contrasting example (your B) that challenges or deepens the original notion.

The steady build of A-A creates a solid foundation, making that final twist all the more surprising and impactful.

Writing Tool 28: Analytical Writing

Imagine you were writing about a watch.

If you write something like, “This is the minute hand, this is the second hand, and this is the clock face,” you’re not really telling the reader anything useful.

That’s called descriptive writing, and it's just information.

Valuable writing goes further. It doesn’t just repeat facts. It finds patterns, unpacks underpinnings, and uses all this information to solve problems that readers care about.

So with the watch, instead of just naming its parts, you could explain how the gears turn, what mechanism allows the hands to move in sync, and how everything aligns with our experience of time.

That’s called analytical writing; it shows the bigger picture.

It's not information but analysis that makes your not only interesting, but valuable.

Writing Tool 29: Beware Zombie Nouns

Consider the sentence:

There was worry that there would be extra homework assigned.

- Who’s doing the worrying?

- Who’s doing the assigning?

- To whom is the homework assigned?

This sentence has been bled dry by zombie nouns. That's when the action is represented not as active verbs but as lifeless nouns.

Instead, punch up your prose by putting real characters in the driver’s seat:

The students worried that the teacher would assign them extra homework.

When you replace vague, static phrases with active verbs and concrete subjects, it brings your writing to life.

Your sentences are more than information; the way you arrange that information gives the reader a lot of information about how they should interpret your sentence, so beware zombie nouns, and instead use active verbs that animate the story into something that the reader can picture–because the best writing is visual, it creates a movie in your mind's eye.

Writing Tool 30: Get Past the Subject Quickly

Here are two sentences–just a warning, the first one kinda stinks.

Since most startup companies pivot their business models at least once during their early years, first-time entrepreneurs who are not certain about the direction of their venture should not commit all their resources to a single strategy.

Did you notice the way that one begins? You have to process a lengthy setup before reaching the core idea:

Since most startup companies pivot their business models at least once during their early years, first-time entrepreneurs who are not certain about the direction of their venture should not commit all their resources to a single strategy.

Compared with this:

First-time entrepreneurs should not commit all their resources to a single strategy if they are not certain about the direction of their venture, because most startup companies pivot their business models at least once during their early years.

Long-winded introductory phrases force your reader to hold on to details while waiting for the main point, which can bog down comprehension.

So if you find your sentence starting with a long introductory clause, consider moving it to the end or splitting it into a separate sentence. This way, your readers get to the heart of your message faster and with less cognitive load.

Writing Tool 31: Avoid Interrupting Subject-Verb Connection

Consider this clunky example:

We must cultivate, if we are to inspire future leaders, a deep understanding of community engagement.

Readers want to get straight to the action—past the verb and onto its object.

But notice how that interrupting clause turns the sentence into a mental obstacle course.

We must cultivate, if we are to inspire future leaders, a deep understanding of community engagement.

As the reader moves through the sentence in time, the interrupting clause makes it hard to see that “cultivate” is directly tied to “a deep understanding of community engagement.”

Instead, try moving the interrupting element to the beginning or the end, depending on what comes next.

If we are to inspire future leaders, we must cultivate a deep understanding of community engagement. These communities may...

or

We must cultivate a deep understanding of community engagement if we are to inspire future leaders. These leaders may...

Readers read most easily when they get through the core of your sentence, so keep the verb closely connected to its object.