Emotion defies logic, but clear writing demands it.

So when describing an emotion, who could be more instructive than David Foster Wallace (1962-2008), the writer in whose voice the marriage of intellect and sincerity was never so fully consummated. "On board the Nadir," Wallace writes,

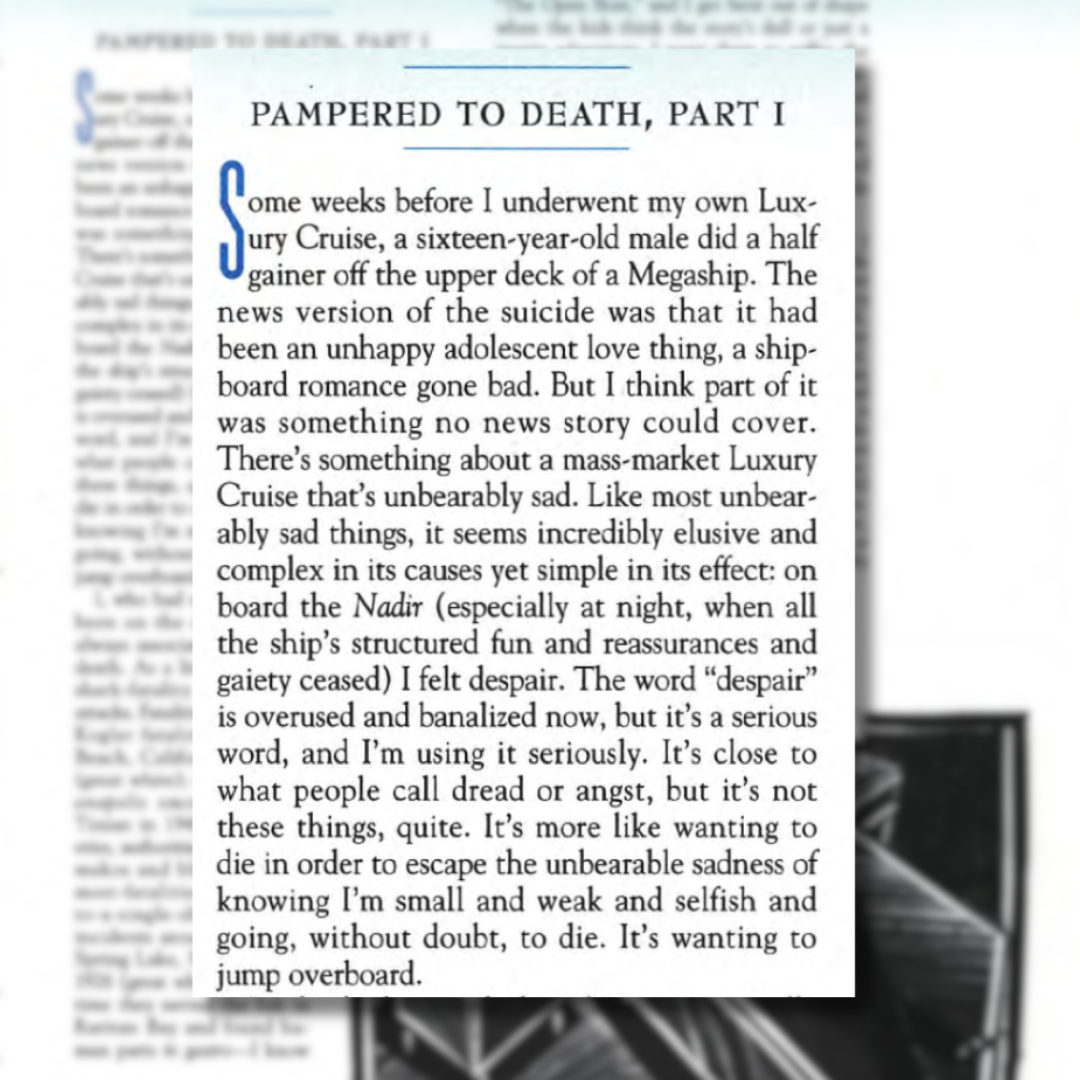

I felt despair. The word's overused and banalified now, despair, but it's a serious word, and I'm using it seriously. For me it denotes a simple admixture–a weird yearning for death combined with a crushing sense of my own smallness and futility that presents as a fear of death. It's maybe close to what people call dread or angst. But it's not these things, quite. It's more like wanting to die in order to escape the unbearable feeling of becoming aware that I'm small and weak and selfish and going without any doubt at all to die. It's wanting to jump overboard.

In this early section of A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again (1996), Wallace sets out to revitalize despair, a useful but worn-out word that comes a long way from the Latin desperare—“down from hope." Aboard the Nadir–a fitting name for a luxury cruise ship that in its course through the Caribbean would take Wallace to the depths of sadness–it is the perfect word. But its overuse has bled the concept of its emotion, leaving behind a hollow cliché.

This won't do for Wallace, who wants to plant despair as the emotional focal point of the narrative. To this end, the author deploys three literary devices that writers can use to write about emotions.

Lexical Cohesion

The first is lexical cohesion, a powerful tool for establishing a context of interpretation.

If the word “despair” has lost its sting, Wallace restores its power by setting it within a conceptual constellation:

- smallness

- futility

- dread

- angst

- yearning for death.

By casting this semantic web around the word, Wallace enmeshes it within a network of meanings that cuts to the bone of the emotion, reanimating the word and stirring in the reader its existential tensions.

Death, in particular, becomes a motif that Wallace emphasizes with deliberate force.

He opens the section by recounting a young man’s fatal leap from the upper deck of the same ship. The moment is unsettling and strange, casting a pall over the 'supposedly fun' scene.

But Wallace doesn’t merely recount the incident—he uses it as a springboard into the deeper emotional undercurrent that courses through his experience on the cruise.

Ironic Juxtaposition

Death, angst, and despair: you won't find these in the brochure to the Nadir.

But in Wallace the grave emotion and the corporate getaway each serve as a frame for interpreting the other. This unlikely arrangement exemplifies the second writing tool, ironic juxtaposition.

We see it in T.S. Eliot's comparison of the night sky with a patient etherized on a table. And in Pulp Fiction, where the mundane conversation between hitmen about hamburgers occurs moments before they carry out a brutal execution.

The strategic placement of contrasting elements whose collocation serves to reveal and amplify their hidden qualities, ironic juxtaposition wrenches the reader awake by reintroducing an all-too familiar concept in a strange, disarming light. For Wallace, who wants to induce in the reader an emotion known only by name, the luxury cruise ship provides the perfect lens through which despair can be seen anew.

Author Persona

Dave Wallace, the person, knew perfectly well what despair was. But David Foster Wallace, the author, appears less sure.

Yet for all the gravitas of its subject matter, Wallace’s tone is strikingly conversational, even folksy. The description of despair is filled with hedges and self-conscious interjections–it's maybe close to this; but it's not that, quite; it's more like this.

Such disfluencies might seem out of place in as careful a writer as Wallace, of whose magnum opus Infinite Jest the author Dave Eggers writes, "The book is 1400 pages long and there's not a careless word in it." Wallace was meticulous. These ums and ahs are strategic, they serve a purpose–namely, they shape his author persona.

Dave Wallace, the person, knew perfectly well what despair was. But David Foster Wallace, the author, appears less sure. The teller of this tale is no Virgil, leading the reader to hell; this is a friend who has been to hell and back, and is trying to make sense of it all over coffee.

In crafting this persona, Wallace shows incredible generosity to his reader. The recipient of a MacArthur genius grant, Wallace goes to great lengths to make himself small in order to make room for his reader, appearing to work out his feelings before us so that we might reach out to say I know exactly what you mean.