Table of contents

The reader is the home of your ideas.

–Eric Hayot

Good writing begins when we consider how our writing will be staged in the mind of the reader.

So before we talk about what good writing looks like, we need to think about what good reading feels like.

In this week’s issue of Writer Science✍️

- What reader’s want

- Writing advice from Frank Zappa

- Today is the day you became a better writer

Was this email forwarded to you? Subscribe here!

Index 📊

543,709: Total number of words in Infinite Jest

238: Words per minute read by the average native English speaker

38: Hours needed for the average native English speaker to read Infinite Jest

31: Number of hours spent per month on Netflix by the average user

12: on Instagram

70.2: Hours needed to watch seasons 1-8 of Game of Thrones

6.4: Percent of people who report having purchased and completed Infinite Jest

6.6: A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

1.9: Hard Choices by Hillary Clinton

Word of the Week 🌟

Feckless (adj)

- Deficient in efficacy, lacking vigorous or determination, feeble

- Careless, profligate, irresponsible

”My feckless teenage son refuses to get a job.”

“A totally great adjective” writes David Foster Wallace in a mini-essay on the usage of feckless, noting that it “appears most often now in connection with wastoid youths, bloated bureaucracies–anyone who’s culpable for his own haplessness.” The subtle connotations and sonority of the word make it not only useful but fun:

“The great thing about using feckless is that it lets you be extremely dismissive and mean without sounding mean; you just sound witty and classy. The word’s also fun to use because of the soft-e assonance and the k sound–and the triply assonant noun form–fecklessness–is even more fun.”

(He’s right; try saying it out loud: feck-less-ness.)

Learn How Brains Organize Ideas 🧠

I stumbled upon a good lesson for writers while playing around with Grok, the AI built in to X.

Grok can generate images along with text, so I asked it to create an image of a sentence that is well known in linguistics:

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

If you’re unfamiliar, the sentence, composed by Noam Chomsky in one of his works on universal grammar, is famous for its semantic ambiguity. It demonstrates the possibility of having a sentence that is grammatically perfect yet lacking any meaning. What on earth would it mean for a green idea to be colorless? Do ideas sleep? What does it mean to sleep furiously? That these questions are impossible to answer is the point of the sentence, but unlike a human reader, the diligent AI was forced to come up with something. But since Grok had no way to visualize an idea sleeping, each time it had to invent a subject–a person, a cat, something that performs the action of the verb sleep.

So it goes for our readers: It's near impossible to imagine actions happening on their own. So to write clearly, make the subject of your sentence a concrete entity, a character who performs the action of the verb.

This is one component of the advice from Scott Adams, which we'll explore below, to learn how brains organize ideas.

The reading mind sees a world in which characters perform action. See for yourself: pick any action, close your eyes, and picture it. What do you see? Is that action happening in some disembodied manner? Do you picture those emphatic little swooshy lines from cartoons just floating around? Or is there a character–a person, an animal, something–performing that action?

Here's a simple rule for writing clearly:

Let’s test it out. Which one of these sentences is easier to understand?

1A: The boy hit the ball.

1B: The ball was hit by the boy.

If you’re like me, you picked (1A). But what makes (1B) so hard to understand?

Close your eyes, and try to imagine this word: hit. What do you see? Nothing.

We can’t imagine an action like hit without also imagining a character who does the hitting.

But, since readers of English read from left to right, (1B) sets up a sequence in which the reader encounters the action (hit) before the thing that performs that action (the boy).

What’s worse, (1B) shifts the action (hit) out of the verb and into a past participle (was hit). The verb expresses not an action but a state of being. In effect, (1B) drains the idea of its life and energy.

By contrast, (1A) uses a sentence structure that matches the reader’s psychology and expectations—it puts a character (the boy) in the subject and action (hit) in the verb.

You might already know those sentence structures are known as the active and passive voices, respectively. But the principle of putting characters in subjects and actions in verbs also applies to sentences like the following. Again, which is easier to understand?

2A: All brains work that way.

2B: That is the way that all brains work.

(2A) is easier to understand because it puts a character (all brains) in the subject position and action (work) in the verb.

(2B) fails the visualization test because its subject carries not a character but a pronoun referring to an abstract concept; and because the action is not in the verb but a noun phrase (the way that all brains work).

Learn how brains organize ideas—it’s good advice. But let’s go one step further: Learn how brains organize ideas, and organize your sentences that way. When we design our sentences around the reader’s psychology, the writing flows.

Amateur writers scoff at the rules of grammar. They tell you that readers don’t care about grammar. They’re wrong.

Grammar is not a list of rules but a set of tools, and expert writers know how to use these tools to complement the organizational patterns of their reader’s brain.

Thoughts & Ideas 💡

- Write like Zappa ▶︎ Knowledge of the instrument and an imagination: that’s all legendary guitarist Frank Zappa brought to each solo. “It's also all you need to write a book or tackle any other creative task,” writes David Moldawer in this week’s issue of Maven Game.

- Maps of Meaning ▶︎ Expert writers–those who use their writing to share their knowledge and expertise–need to understand how to structure their information at multiple levels of resolution. Francis Miller’s concept of multi-level content provides a helpful, visual solution.

- Writing Is Thinking ▶︎ Since writing is a way of figuring out what we think, we should think twice before outsourcing that process to generative AI, writes Director of the Harvard Writing Center Jane Rosenzweig in Four Rules for Writing in the Age of AI.

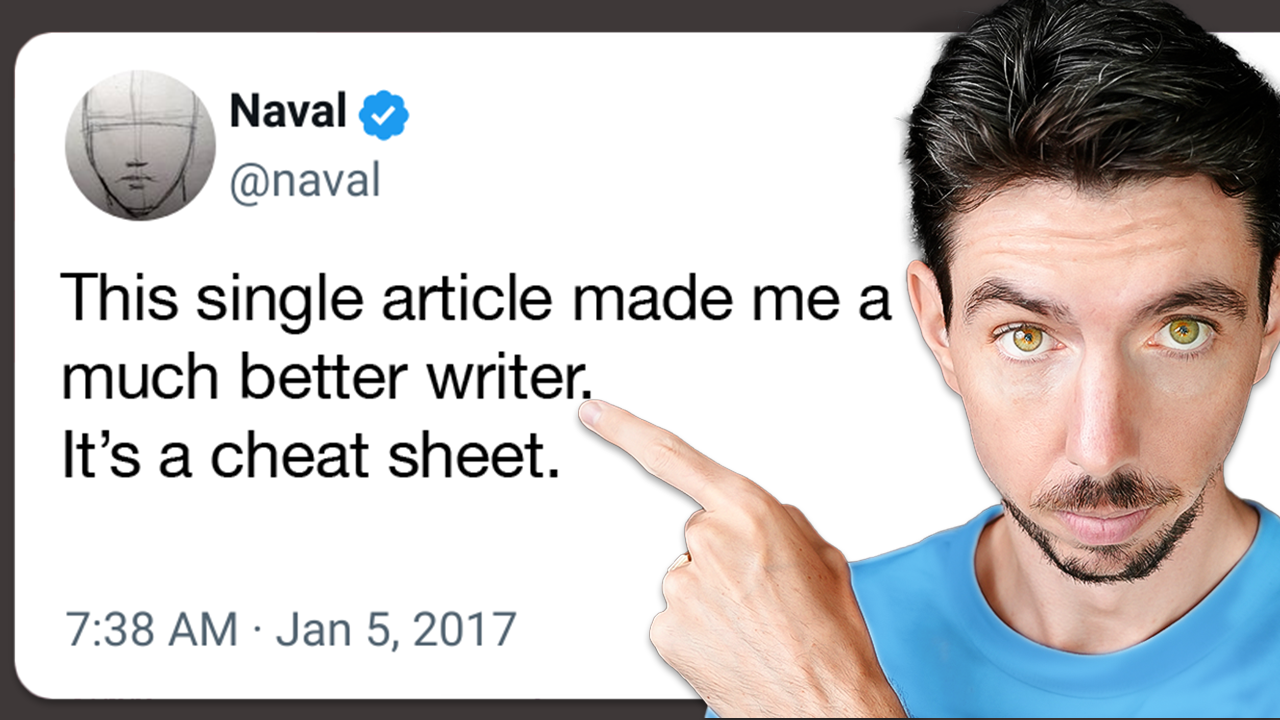

The Day You Became a Better Writer ✍️

The lesson from today’s issue of Writer Science came from a blog post by Scott Adams titled The Day You Became a Better Writer.

It’s a great article, but there is one problem with it. It introduces some great principles for clear writing, but in an attempt to demonstrate the principles of clarity and simplicity that it espouses, the author made it a little too short and elliptical. In failing to explain the rationale behind its prescriptions, the article becomes just another inscrutable list of writing rules.

I wanted to understand why these principles work so well, so I took a deep dive into the article. In this week’s video, expect to learn…

- Kill your darlings ▶︎ How to write persuasively by writing clearly;

- Trigger curiosity ▶︎ How to use 4 principles from the psychology of curiosity to keep your reader motivated;

- Learn how brains organize ideas ▶︎ How to organize your sentences to complement the psychology of your reader.

We won’t simply be rehashing these rules but analyzing them from the perspective of the reading mind.

The Day You Became a Better Writer

Editor’s Choice 🏆

Closing Thought 💬

This week I started reading Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon (2021) by Mark McGurl. And it’s got some pretty interesting ideas, about the effect of online retail on literary production.

But if I’m honest, it’s not the ideas of the book I’m interested in. It’s the style. Mark McGurl is one of my favorite academic stylists. I would read a Terms of Service agreement if it was written by McGurl.

So let me ask you:

what author do you read more for the style of their writing than the content?

Let us know in the comments! 💬

Enjoy this newsletter? Forward to a friend, leave a comment, or hit REPLY to share your thoughts. I’d love to hear from you!

Want more writing tutorials? I’ve been using X to test out new lessons and ideas. You can follow me @writerscience.

Support My Writing by leaving a tip. At this early stage of my journey into content creation, your support means so much.